Why Antarctica needs our protection

Cruising through the ice by zodiac

Humanity has only been visiting Antarctica for a very brief time. Captain James Cook’s ship HMS Resolution made the first recorded crossing of the Antarctic Circle in 1773, and the first person to step foot on the continent did not do so until nearly 50 years later. Even today when there are around 80 Antarctic research stations, only around 1000 people over-winter every year and there is no permanent human population. But numbers of visitors are on the increase, and this brings an increased burden of responsibility to protect this long-isolated corner of the globe.

Like anywhere in the world, travel to Antarctic carries an environmental cost through carbon emissions, from flying to gateway cities to the fuel used by the ships needed to get around. Conversely, scientists are also beginning to understand the role that the Southern Ocean around Antarctica acts as an important carbon sink. For these reasons alone it is vital that we understand the role we can play as responsible travellers to help protect this extraordinary but fragile part of our planet for future generations.

Regulating tourism in Antarctica

Antarctica is a place with no flags – it relies on the collaboration of all nations to protect it. In 1959 the Antarctic Treaty was signed to preserve the continent as a place of peace and science. In 1991 when Antarctic tourism was still in its infancy, a group of tour operators founded the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), a voluntary organisation that advocates for safe and environmentally responsible travel to Antarctica, in line with the tenets of the Antarctic Treaty. We are proud to be an associate member of IAATO.

IAATO has developed a set of guidelines for responsible tourism to Antarctica, as well as protocols for expedition cruise ships sailing to the white continent. These range from biosecurity protocols during a visit to codes of conduct needed at different landing sites. IAATO has also introduced monitoring of the fuel consumption of the polar fleet in order to meet the International Maritime Organisation target of at least 50% emissions reductions by 2050 compared with 2008 levels and the global goal of net zero before 2050.

As associate members of IAATO we strictly adhere to their guidelines throughout our work. For us, that means everything from ensuring the photos on our website reflect the wildlife-watching guidance, to guaranteeing every single one of our customers receives IAATO's information booklet before departure – you can find these in your Adventure Planner.

We only work with tour operators that are part of IAATO, and who abide by regulations that will protect the continent we love. To keep up to date, every year we join hundreds of others at IAATO's annual meeting to understand the latest best practices, changing guidelines, and to contribute to the conversation about sustainable tourism in Antarctica.

Swoop says

Ensuring travellers return from Antarctica as ambassadors is central to both Swoop and IAATO's mission to raise awareness of this fragile environment. Few places are better for reminding us of our planet's majesty and the need to protect what we have in a time of climate change.

Alex Mudd Head of Swoop Antarctica

Antarctica's ecosystem

Two seals resting on an iceberg

The cold waters of the Antarctic convergence that constantly circle the continent and the vast buffer of sea ice that guard its shores have left Antarctica as one of the last regions on the planet to remain largely unimpacted by invasive species from the outside. As a result, the continent's ecosystems have been left to evolve undisturbed. Antarctica’s seas teem with life in a food web that reaches from the smallest phytoplankton to the largest whales, but the picture on shore is very different. Terrestrial biodiversity is incredibly low, and is restricted to a handful of simple plants such as lichens, mosses and liverworts and no animal species larger than the tiny Antarctic midge, an endemic flightless insect that is specially adapted to the frozen climate.

From the moment the first explorers brought sledge dogs to Antarctica at the beginning of the 20th century, there has been a risk of damaging these fragile systems through the introduction of non-native species. Although the Antarctic Treaty mandated the removal of the last remaining dogs in 1994, the ever-growing number of people and ships visiting Antarctica, plus the increased warming being experienced in the polar regions, mean that there is always the possibility of the accidental introduction of invasive plants and animals.

Tackling non-native species

Baiting for rats on South Georgia (Image: Tony Martin/South Georgia Heritage Trust)

The risks posed to Antarctic biodiversity by non-native invasive species is best illustrated by South Georgia. Years of visits by sealing ships and the establishment of whaling stations in the early 20th century provided ample opportunities for alien species to damage its ecosystem. Reindeer introduced as a source of meat for the whalers overgrazed native fauna, while rats and mice wreaked havoc on bird populations. Even the island’s dead played their part: foreign soil used for burial in the cemeteries brought seeds for invasive plants.

In recent years the South Georgia Heritage Trust ran a successful £10 million habitat restoration project in one of the most challenging environments on earth to eradicate rodents from the island. Reindeer were similarly culled or relocated to the Falkland Islands. After five years of work, South Georgia was finally declared rat-free in 2018 and numbers of rare species like the South Georgia pipit and pintail duck are increasing every year. Much of the funding for this successful programme came from the polar cruise industry and its passengers. Work continues to control non-native plant species, but thanks to projects like this and careful management of the waters around the island, South Georgia today has been declared that rarest of things: an ecosystem in recovery.

Unwanted hitchhikers

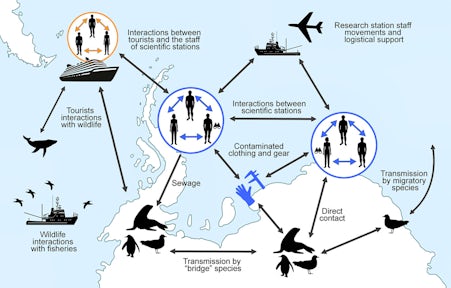

Possible transmission routes for invasive species to Antarctica (Image: Shavawn Donoghue, Nov 2021)

To date the impact of non-native species on the Antarctic continent itself has thankfully been minimal and restricted to the ice-free areas of the South Shetland Islands. A tiny species of introduced fly has been recorded in the Admiralty Bay area on King George Island, surviving around the sewage system of certain research bases. But as rising temperatures impact ice coverage, the risk of accidental introduction becomes ever more present.

One area of increasing concern is the risk of biofouling from ships. As more vessels enter Antarctic waters, there is the chance that they could unwittingly bring with them hitchhikers attached to their hulls such as mussels, barnacles, crabs and algae. There is a particular fear attached to the accidental transfer of cold-adapted species on vessels (including research and cruise ships) that regularly travel between the polar regions. Crab and mussel species that are absent in Antarctic waters and therefore have no natural predators could easily cause great damage to the delicate underwater ecosystems. Biosecurity measures including the cleaning of ships’ hulls are already in place in recognised gateway ports including Ushuaia, but increased monitoring is required as the polar seas become ever more popular.

What you can do as a visitor

A mandatory onboard biosecurity briefing prior to arrival in Antarctica

We strongly encourage all our travellers to become familiar with the IAATO visitor guidelines prior to departure for Antarctica. Most of the guidelines are common sense, but advance reading will help prepare you for the briefings about biosecurity and how to behave during a landing that you'll receive once you're on board your ship.

Always listen to your expedition leader and guiding team. They are there to help you and ensure you have the best experience while also minimising the impact of your visit on the continent. Take their advice seriously: we all need to stand up for Antarctica.

Before you take your first steps in Antarctica, you will be encouraged by the crew to vacuum and clean all gear that you will take off the ship. This includes all outer layers and any day packs or camera bags, and giving your boots an extra scrub if needed. Ships will often hold a 'biosecurity party' where the guides will help you inspect all your gear to make sure it's clean, and you may be asked to sign a declaration form saying that you've understood and followed the biosecurity procedures. All gear that may come into contact with the ground is treated with Virkon disinfectant to prevent the accidental transfer of pathogens (this will not damage your clothes or other items).

If you're visiting South Georgia you'll find that biosecurity checks between landing sites are as stringent as when you first arrive. The island's human history means that many landing sites have non-native plants, making the prevention of accidental seed transfer even more important. The Government of South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands has its own biosecurity rules and carries out regular spot checks on expedition cruise ships to make sure they are being adhered to.

Similar biosecurity guidelines are also in place for the Falkland Islands, and visitors are encouraged to familiarise themselves with the Falkland Islands Countryside Code before their trip.

Before your first landing in Antarctica

Getting ready to clean gear before a landing

Preparation for your arrival in Antarctica begins when you are packing for your trip (take a look at our packing guidelines for some tips). Although the Virkon disinfectant used on all ships won't damage your items, it will make them wet, so we recommend taking a dry bag for when you're on shore, which will also help protect your gear from spray on a zodiac trip. If you can, avoid bags with mesh and velcro: these are perfect for accidentally catching seeds and dirt, so you should carefully pull out any organic debris before you board the ship.

Passengers must go through a Virkon foot bath prior to boarding their zodiacs for a landing. Boots are scrubbed on returning to the ship to ensure nothing is brought on board – an important step if you've visited a site covered with lots of penguin guano!

Swoop says

A bent paperclip or a pair of tweezers might be the most useful thing you pack for your trip: they're perfect for removing organic material trapped in velcro or backpack mesh.

During a landing

Following wildlife watching guidelines on Cuverville Island in Antarctica

Each landing site you visit in Antarctica has its own specific visitor guidelines as outlined by the Antarctic Treaty, and your guides will brief you on specific codes of conduct when you land, such as restrictions on where you are allowed to walk. These are for your safety as well as that of the local wildlife. You'll be asked to follow IAATO guidelines for wildlife watching, including specific guidance for certain species.

The key rule is you must always minimise your impact on wildlife behaviour. This includes keeping a minimum distance of 5m away from wildlife and quietly retreating if approached, and always giving animals the right of way. As well as keeping wildlife safe, this allows you to observe the unaltered behaviour of the animals – something you've travelled a long way to see.

As per IAATO regulations you should not sit, kneel or lie on the ground or snow, or place bags on the ground. The only items in contact with the ground should be the soles of your boots. Squatting or crouching down just off the ground is also not permitted. For photographers looking to get a lower angle, we recommend bringing a camera with an articulated screen.

If you trip or slip over at any point, please make sure anything that touched the ground is disinfected when you return to the ship, paying special attention to your clothing and washing your hands carefully. Trekking poles and tripod feet must also be thoroughly cleaned, just like your boots. This is everyone's responsibility, so if you see someone in your zodiac forgetting to do this amid the excitement of completing a landing, please speak up: your guides and Antarctica's wildlife will thank you.

Typical biosecurity checks following a landing in Antarctica

Avian Flu

Potential chains of avian flu transmission in Antarctica (Image: Andrés Barbosa/Creative Commons)

Avian Flu (avian influenza) is a virus that exists in wild birds and is spread by faeces and respiratory secretions. In many parts of the northern hemisphere, it already has decimated domestic poultry populations as well as wild birds – particularly seabirds. It carries a very low risk to humans but a much higher risk to animals. The virus can survive for long periods in sub-zero conditions and can easily be carried on clothing and other kit.

In October 2023, Avian Flu was detected on the island of South Georgia, leading to restrictions being put in place for some landing sites for that season, but after receiving scientific advice, all landing sites have remained open for the current 2024/25 season. For more information, see our Avian Flu in South Georgia page.

As of mid-January 2025, the Antarctic Peninsula has had a small number of confirmed cases of Avian Flu, resulting in seven landing sites being restricted to zodiac cruising only to manage any potential risk. However, Antarctica is vast, and bursting with spectacular locations to explore and flexibility has always been key in expedition cruising. We are confident that this will not impact the experience of those on expedition voyages between now and the end of this Antarctic season at the end of March.

IAATO has worked with scientists and other researchers to introduce additional biosecurity protocols that came into effect in the 2022/23 season. These protocols are mandatory for all IAATO operators and their staff working in Antarctica. These rules will be included as part of your onboard biosecurity briefing but include the introduction of mandatory minimum distances between visitors and wildlife, and extra cleaning and disinfecting of any item that may come into contact with the Antarctic environment.

Behind the scenes, there has been much hard work to ensure that polar guides have received training on recognising Avian Flu in wild bird populations. During your visit, guiding protocols include extra scouting of landing sites before deciding to allow passengers to disembark, as well as streamlined reporting about landing sites between ships and IAATO throughout the season.

While the biosecurity procedures you'll be asked to adhere to may initially sound daunting (especially prior to travel), they quickly become a routine part of your polar visit. By sticking to the protocols and any extra advice from your guides, you can take pride in knowing that you're helping to keep Antarctica and its penguins and other wildlife safe from Avian Flu and other pathogens.